Author: Irene Pepperberg

ISBN-10: 0061673986

ISBN-13: 978-0061673986

APA Style Citation

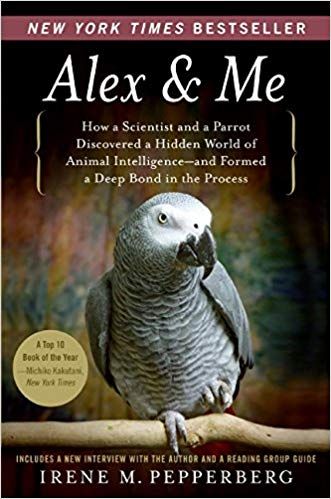

Pepperberg, I. (2009). Alex & Me: How a scientists and a parrot discovered a hidden world of animal intelligence—and formed a deep bond in the process. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Buy This Book

https://www.amazon.com/Alex-Me-Scientist-Discovered-Intelligence/dp/006167398

| alex_and_me_activity.pdf |

Do birds have language or is the story of Alex & Me for the birds? The studies of Dr. Irene Pepperberg revolutionized the way we think of bird brains. She worked with an African Grey parrot named Alex for over three decades as she tested his verbal, mathematical, and cognitive abilities. The book starts with the public acknowledgement of his death in 2007. For example, Diane Sawyer did a 2.5 minutes segment on ABC’s Good Morning America. She commented “And now I have a kind of obituary and I want to inform the next of kin about a death in the family. And, yes, the next of kin would be all of us.” A website was setup for condolences and many cards were received. One card came from Penny Patterson and friends, owner of the famous Koko gorilla who used sign language to communicate with humans. “Koko sends a message with the color of healing. Please know you are all in our thoughts and prayers- Alex’s passing is a great loss to all.” Below Penny’s words was an orange squiggle, done by Koko himself. Then the story rewinds back to Dr. Pepperberg as a child receiving her first bird as a present and winds through the trials and tribulations of her career as she explores animal thinking.

Dr. Pepperberg’s love for birds started as a young child. She grew up as an only child with a distant mother and didn’t really fit in with her peers. With a surprise gift of a parakeet for her fourth birthday and exposure to Dr. Doolittle, her journey working with birds started. Rather than taking the traditional route of studying biology, she fell in love with the periodic table of elements and followed the path of chemistry. At 16 years-old she headed off to MIT to study chemistry, but birds remained an important part of her life. After getting married and losing her home to a fire, Pepperberg was exposed to PBS’s NOVA television series, which was devoted to science and nature. Her passion for animals was reignited and she cast chemistry aside. Quickly, she became engrossed in bird behavior, child cognition, and language. At this time scientists believed animals were robotic automations who mindlessly responded to stimuli in their environment. However, new science was changing this view and Dr. Pepperberg wanted to be involved in this revolution.

In 1977, Pepperberg and her husband moved to Indiana where she spent seven years at Purdue University. Shortly after arriving she selected her first African Grey parrot from a Chicago pet store. It did not start well because Alex was uneasy and scared of his new environment, but within a few days they became more familiar with each other. He came out of his cage and would perch on her arm. Dr. Pepperberg called him Alex, which was short for Project ALEX: Avian Language Experiment. Soon after she switched it to Avian Learning Experiment and planned to develop parrot-human communication using labels, as was being done with apes. She gave Alex objects, such as paper and pieces of wood, to explore his preferences. She also used a modified form of training based on social context. Two trainers would take turns asking each other about an object’s label, with Alex observing. At the time operant conditioning was the preferred method of training. Dr. Pepperberg applied for a National Institute of Mental Health grant with the desire to replicate in a Grey parrot the linguistic and cognitive skills that has been previously achieved with chimps. The NIMH proposal was approved but no money was available to fund it. Dr. Pepperberg refused to give up.

Alex progressed quickly, within a year he had 80% accuracy in labeling seven objects and was beginning to learn his colors. He could also identify 3-corner pieces and 4-corner pieces of wood. Dr. Pepperberg tried to have her studies published in both American and British journals, but there was no significant interest. At this time the field of animal thinking was being questioned. These attacks on the field only caused Dr. Pepperberg to continue her rigorous training in testing her Grey parrots. She came from the hard sciences and wanted to have scientific proof of her theories. She insisted on repetitive trials before she could say with statistical confidence that Alex had cognitive ability. Empirical results with animal studies were necessary to avoid a “Clever Hans” situation, where researcher bias influenced the results. Check out the book review "The Horse That Won’t Go Away: Clever Hans, Facilitated Communication, and the Need for Clear Thinking.” (https://booksforpsychologyclass.weebly.com/blog/the-horse-that-wont-go-away-clever-hans-facilitated-communication-and-the-need-for-clear-thinking).

Dr. Pepperberg was able to live off meager National Science Foundation grants. By 1981, Alex started to get public attention and continued to advance at an astounding rate. He could understand the concept of color and shape as categories that contained labels. He learned to use “I’m sorry” in an upsetting moment. Alex continued to advance and soon he combined parts of words to make a new word. For example, he called an apple a “bannerry;” banana + cherry = banerry. He also became bored easily. When asked about the color of an object, he would sometimes give every color he knew, skipping only the correct color. While his sense of humor was not science, it was telling. Something was going on in his little bird brain. He knew what he was saying, and his comprehension was equal to chimpanzees and dolphins. His next challenge was to determine if objects were the same or different. It took months to train him, but he was correct 75% of the time when asked about the same “shape” or “color.” When novel objects were presented, such as a color he could not label, he was correct 85% of the time. He had outwitted chimps, by not only identifying if two objects were similar or not, but by verbalizing how they were the same or different in color, shape, or material.

In 1991, Dr. Pepperberg’s position at Northwestern came to a close, and her marriage fell apart. She was not taken seriously as a female scientist, and she struggled to gain employment. Alex got a fungal infection in his chest cavity and lungs. He was very sick and had to have surgery. It took over a year for him to recover and the whole ordeal was quite taxing physically and emotionally on Dr. Pepperberg. Finally, she decided to take a position in Tucson, Arizona and moved with Alex alone to the southwest.

In Arizona, Pepperberg continued her work with Grey parrots. She expanded her studies with two more Greys- Alo and Kyaaro (Kyo) and created a culture balanced with playfulness and careful scientific study. In 1991, she established the Alex Foundation to raise money to support and spread the word of her work. Alex participated in a study on recognizing and understanding Arabic numbers. His vocalizations sounded like English, but did they have similar acoustic properties? Sonograms proved that his vocalizations looked identical to human speech. In 1995, Alo was sent to live with a friend, and Dr. Pepperberg got a new 7.5-week-old Grey parrot, which she named Griffin. Greys are territorial, and Alex did not take well to the new parrot. Alex was the boss of the lab and filled with entitlement. His perch always had to be higher, and he needed attention first or he would not work for the day. Dr. Pepperberg would often take Alex home, but in 1998 he saw western screech owls building a nest outside her window and wanted to leave. She pulled the drapes, still he cried “Wanna go back…wanna go back.” This was a perfect example to demonstrate that Alex had mastered the concept of object permanence.

As Alex gained public exposure, he stirred jealousy amongst Dr. Pepperberg’s colleagues. This combined with other circumstance no longer made Tucson a good fit. When Pepperberg was asked to give a lecture on Alex at MIT’s Media Lab, she accepted a position and left Alex behind in Arizona for one year. It was here that her creative side was allowed to blossom. She worked on an electronic bird sitter, a smart nest that tracked Greys in Africa, and a system that enriched parrot’s vocab and worked with autistic children. It was at MIT that she got Wart, a 1-year-old Grey. In 2000, she taped another episode of Scientific American Frontiers, called Pet Tech, with Alan Alda. Alex was also being trained to sound out phonemes with colored plastic refrigerator letters. During one interview he would answer her questions, but then demanded a nut. Suddenly he said, “Want a nut…nnn…uh…tuh.” He leaped beyond the expected results of his training and was able to demand a nut while using phonemes. Dr. Pepperberg received a five-year renewable contract as a research scientist at Media Lab and she left her tenured job in Arizona. Only three months later, in mid-2001, she and 30 others were let go. Without a lab, her parrots had to move in with friends for the next five months. Alex and Griffin became subdued at this time.

Dr. Pepperberg ended up receiving a position at Brandeis University in Boston. It was challenging at first, but she enlisted Alex as Griffin’s trainer and soon her work was back on track. By 2003, Alex knew numbers 1-6. He had a concept of zero and soon after was learning addition. Over the next six months, his addition accuracy was 85%, and he was on par with small children and chimpanzees. When presented with a green Arabic numeral 5 next to three blue wooden blocks and asked which color is bigger, he replied “green” showcasing his ability to judge the question according to number. Chimps cannot do this without extensive training. He was also tested on the Muller-Lyer illusion, and he fell for the optical illusion in a similar way as humans. In 2005, Dr. Pepperberg moved on to Harvard.

On September 5, 2007, Alex bid Dr. Pepperberg goodnight with, “You be good, I love you.” Pepperberg answered, “I love you, too.” Alex followed with, “You’ll be in tomorrow?” Dr. Pepperberg responded, “Yes, I’ll be in tomorrow.” This was their usual evening exchange. The next morning Dr. Pepperberg received the alarming email that he had passed away in the evening, 20 years before his expected life expectancy. Dr. Pepperberg believes the greatest lesson Alex taught her was patience. But the greatest lesson to be learned was that animal minds are more like human minds than was once believed. Any animal limitation thrown at Alex, he was able to accomplish. If only his life did not come to an abrupt halt, he may have accomplished so much more.

Other Related Resources

Alex Foundation

https://alexfoundation.org/

How Irene Pepperberg Revolutionized Our Understanding of Bird Intelligence

https://www.audubon.org/news/how-irene-pepperberg-revolutionized-our-understanding-bird-intelligence

NY Times- Alex’s Death

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/10/science/10cnd-parrot.html

NY Times- “Brainy Parrot Dies, Emotive to the End”

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/11/science/11parrot.html?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=418229D220C538443336F917ABCAFDE5&gwt=pay

NPR- Alex’s Death

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14293868

NY Times- “Alex the Parrot”

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/12/opinion/12wed4.html?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=B20EDBF8BC268546B6755365A542F53F&gwt=pay&assetType=opinion

NY Times- “Alex Wanted a Cracker, but Did He Want One?”

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/16/weekinreview/16john.html

Economist- “Alex the African Grey”

https://www.economist.com/obituary/2007/09/20/alex-the-african-Grey

Alex the Parrots’ Final Experiment

https://www.aaas.org/alex-parrots-final-experiment

Alex the Parrot

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXoTaZotdHg

Psychological Figures and Concepts

Aristotle

Nim Chimpsky

Noam Chompsky

Charles Darwin

Allen and Beatrice Gardner

Jane Goodall

Clever Hans

Koko

Konrad Lorenz

Jean Piaget

David Premack

Washoe

Animal cognition

Animal subjects

Assimilate

Autism

Babbling

Behaviorism

Biology

Birds

Chimps

Cortex

Empathy

Innate

Language

Mirror tests

Muller-Lyer illusion

Object permanence

Operant conditioning

Optical illusions

Phonemes

Psychotic

Second-language acquisition

Statistical sample

Visual perception

RSS Feed

RSS Feed